Why DeFi governance (almost) always fails?

Swan, Pike, and Crawfish, with good fortune, Once joined to pull a loaded cart; All three got harnessed to perform their part. They pull with all their might - but gain not one iota! The load is rather light if they could jointly try – Yet Swan is reaching for the sky, Crawfish is moving backwards, Pike, into the water. Which one is right or wrong – to reckon isn't fair, Save for the cart still being there.

I. Krylov «Swan, Pike, and Crawfish»

Now imagine that cart is on fire, everything around is also on fire, and instead of Pike, Swan and Crawfish, it’s hundreds (if not thousands) of retail investors, whales, VCs and team members. That’s what DeFi governance is often like.

In discord of pretty much any DeFi community, you can often ask people asking something along the lines of “when governance?” or “when vote”, but the reality is much more complicated than simply setting up a governance forum and letting users vote on proposals. Let us explore some of DeFi’s governance shortfalls from the past to see if there are any lessons to be learned.

Justin Sun’s COMP attack

Compound Finance is one of the biggest lending platforms in DeFi. Its governance token $COMP can be used to vote on proposals about adding new collateral types, increasing liquidity mining rewards, changing LTV etc.

This February, Justin Sun borrowed 90k $COMP and attempted to pass the governance proposal to whitelist $TUSD as collateral with a collateral factor of 80% and start distributing rewards to $TUSD depositors. The proposal saw a major community pushback and ultimately failed, but still demonstrated how dangerous this type of behaviour could be.

It is assumed that governance token holders have a stake in the protocol’s success and have the protocol’s best interests in mind, as they have risked their funds to borrow the token. This assumption, however, rarely holds true, for example, in cases where interested parties can simply borrow their governance power for someone else.

Beanstalk exploit

Sometimes the governance power can be “borrowed” completely unexpectedly and with catastrophic outcomes for protocols.

This, unfortunately, was the case for the Beanstalk Farms - stablecoin protocol with $BEAN token pegged to $1 and non-tradable governance Stalk token, which is generated upon deposits in the protocol.

Earlier this year, an attacker used flash loans to borrow ~$1B worth of stablecoins from AAVE, which they then deposited into the protocol, acquired 70% of the government power and used to pass a malicious on-chain proposal that transferred all protocol funds to them.

Beanstalk had multiple safeguards, such as waiting periods for proposals. But as the governance process was completely decentralised, an attacker was able to circumvent all of them without getting stopped.

Fully permissionless governance matches the spirit of DeFi perfectly. However, for it to remain safe for now, there must be some centralised party (usually the development team) who would oversee the process.

Solend account takeover

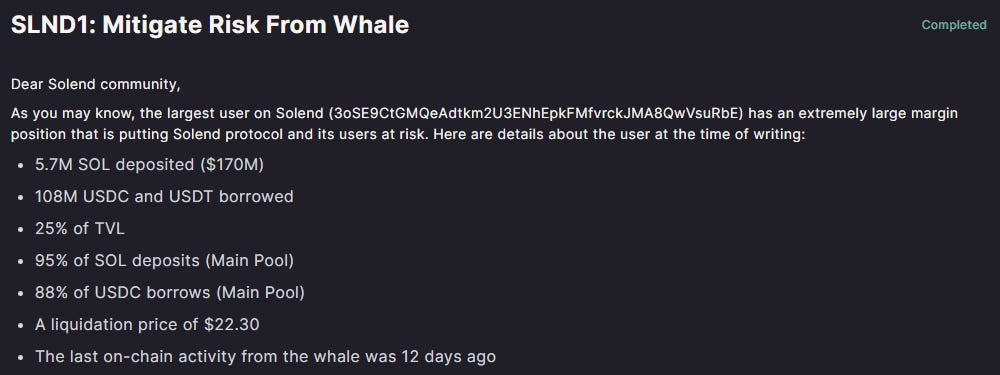

On the other hand, introducing “centralised” elements into decision-making for DeFi protocols can lead to some dangerous and controversial results. Solend (the biggest lending platform on Solana) was able to experience them first-hand this June.

Even though the governance for $SLND token holders existed since last year, the first proposal was launched only when the protocol was put at risk of acquiring bad debt. The proposal essentially offered to take over an account of a large borrower and liquidate them in an OTC deal. The aim was to avoid on-chain liquidations and potentially halting the whole blockchain due to them.

The intentions were good, but using governance to take over someone else’s account on the DeFi platform presented a dangerous precedent and went against the “spirit of DeFi”. Despite major pushback from the community, the proposal passed with 87% of votes coming from one address.

This further showed how “centralised” the DeFi governance can be and how some protocols might use it as a facade to push the decisions on the team's behalf. In the case of Solend, this behaviour can be justified by extreme urgency. The protocol and the whole chain were at risk, so spending weeks discussing potential solutions with the community would have been counter-productive. From that, we can conclude that proper DeFi governance only makes sense for non-urgent and/or less important matters.

Fei/Rari mess

Sometimes, even non-urgent matters are very hard to settle through DeFi governance simply because of how many moving parts there are and how many different parties with different interests are involved.

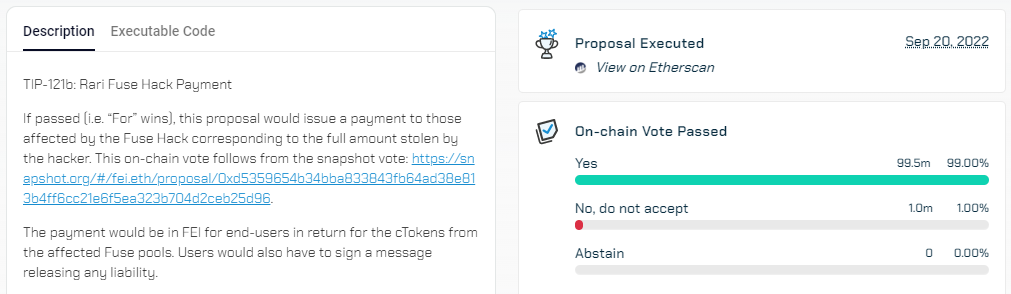

When Rari Capital was hacked for $80M in April, the solution seemed obvious, Tribe DAO (which Rari was a part of) had enough funds to repay all of the victims. However, the reimbursement didn’t happen even though the vote to make everyone whole passed.

It took more than four months and the dissolution of the whole DAO to finally pay what is owed to all of the hack victims with a proposal executed on September 20th.

Why did it take so long? The first obstacle was DAO’s structure itself - Tribe was through a merger of 2 different protocols (Fei and Rari), which as a result, had different opinions and different interests. The second was the involvement of other DAOs - Frax, Olympus and some others lost money in Rari exploit. In addition to that, shortly after the hack occurred, the market conditions worsened, resulting in a change of sentiment.

Finally, the sheer amount of entities involved made it hard to agree on anything. besides already mentioned Tribe DAO members, hack victims, and third-party DAOs, there were Fei Labs (the legal entity behind Fei protocol), $TRIBE token holders, $FEI token holders and VCs, who all had their own agenda and fought for their own interests.

Ultimately, even though the proposal to refund victims of the exploit was initially accepted, there was no way for the community to enforce it. Actually, implementing it was left up to the founding team. Once again, decentralised governance was shown to be more of a gimmick rather than an actual working mechanism able to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion for everyone at a reasonable enough time.

Balancer gauges misalignment

So maybe decentralised on-chain governance could work for one specific aspect of a protocol, such as directing emissions to liquidity pools? We’ve already written about gauges and ve-tokenomics in the summer, but are these systems actually good governance mechanisms?

Turns out, not always. Theoretically, the emissions should be directed to the pools that generate the largest volume and, as a result, the largest revenue for the DEX. In practice, however, the incentives are misaligned. LPs are encouraged to vote for the pools they are LPing in, not the ones that are beneficial for the protocol as a whole.

For example, at Balancer, BADGER/WBTC and stMATIC/MATIC pools used to receive 48% of all rewards while contributing only 0.5% to the protocol’s total volume. So while ve gauges are the most common form of on-chain DeFi governance and some protocols (e.g., Curve) found large success with them, they are clearly not a panacea nor a fit-all solution.

Conclusion

It is incredibly hard to build a governance system that is decentralised, secure from exploits and bad actors, productive and generates actual value for the protocol. But do all of these (and many others) failures mean that the dream of DeFI governance is futile and it is unachievable? Certainly not. However, it means that the protocols should tread carefully when they want to implement any form of governance, lest they want to repeat the mistakes of everyone that came before them.